Symbols, Formula And Equations SS1 Chemistry Lesson Note

Download Lesson NoteTopic: Symbols, Formula And Equations

ELEMENTS AND SYMBOLS

An element is a substance which cannot be split into simpler units by ordinary chemical processes. There are over one hundred known elements.

SYMBOLS OF ELEMENTS

There are three ways in which symbols of elements are derived.

- From the first letter of the name of the element eg

- Hydrogen (H)

- Oxygen (O)

- Iodine (I)

- Fluorine (F)

- Nitrogen (N)

- Sulphur (S)

- Carbon ( C )

- Phosphorus (P)

The first letter is written in capital letters and one other letter from its name is written in small letters i.e.

- Chlorine (Cl)

- Bramine (Br)

- Calcium (Ca)

- Aluminium (Al)

- Magnesium (Mg)

- Berylium (Be)

- Helium (He)

- Neon (Ne)

- Lithium (Li)

The symbols of some elements were derived from their Latin names eg

- Mercury ie Hydragyrium (Hg)

- Sodium ie Natrium (Na)

- Iron ie Ferrum (Fe)

- Copper ie Cuprum (Cu)

- Silver ie Argentum (Ag)

- Tin ie Stannum (Sn)

- Gold ie Aurum (Au)

- Potassium ie Kalium (K)

- Lead ie Plumbum (Pb)

CLASSIFICATION OF ELEMENTS

Elements can be classified into metals and non-metals.

Examples of metals include iron, zinc, tin, aluminium, copper etc.

Examples of non-metals are Chlorine, oxygen, sulphur, fluorine, hydrogen etc.

Some elements however possess the properties of metals as well as non-metals. They are called metalloids, examples are silicon and germanium.

THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN METALS AND NON-METALS

| S/N | METALS | NON-METALS |

| 1 | They are solids except for mercury | They can be solids, liquids or gases |

| 2 | Good conductors of heat | Poor conductors of heat and electricity (except graphite) |

| 3 | Malleable | Brittle |

| 4 | Ductile | Non-ductile |

| 5 | Shiny | Not shiny |

| 6 | Often very dense | Usually less dense |

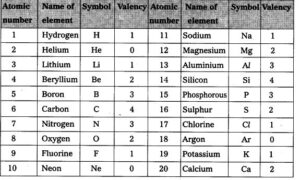

VALENCY

Valency is the combining power of an element. It can also be defined as the number of hydrogen atoms that can combine with or replace one atom of that element.

The valency of an element depends on its structure of that element. At times it corresponds to the number of electrons in the outermost shells called valence electrons.

Below are the valencies of some elements:

| Element | Symbol | Valency |

| Aluminum | Al | -3 |

| Argon | Ag | Nil |

| Calcium | Ca | +2 |

| Chlorine | Cl | -1 |

| Sulphur | S | -2, -4, -6 |

| Sodium | Na | +1 |

| Magnesium | Mg | +2 |

| Copper | Cu | +1, +2 |

| Carbon | C | -2, -4 |

| Barium | Ba | +2 |

| Silver | Ag | +1 |

| Iron | Fe | +2, +3 |

Valencies have either positive or negative values showing whether electrons are gained or lost. If an element gains electrons, its value is negative but positive when it loses electrons.

Generally, metals exhibit positive valencies while non–metals tend to have negative valencies. Some elements exhibit more than one valency. Valency can also be called oxidation number or state.

RADICALS

A radical is a group of atoms having an electric charge either positive or negative which keeps its identity and reacts as a single unit. Any small group of atoms carrying a negative charge is called an acid radical. Examples of acid radicals include S042-, C032-, N03-

The valency of a radical corresponds to the charge it carries.

| Radical | Formula | Valency |

| Ammonium | NH4+ | +1 |

| Hydroxide | OH- | -1 |

| Trioxonitrate (v) | NO3- | -1 |

| Dioxonitrate (v) | NO2- | -1 |

| Trioxocarbonate (iv) | CO3(2-) | -2 |

| Tetraoxosulphate (vi) | SO4(2-) | -2 |

| Hydrogen trioxocatbonate | HCO3(2-) | -1 |

ASSIGNMENT

- Define (i) valency (ii) Radical

- Write the valency of: a) Oxygen (b) Potassium c) Sulphur d) S042- e) NH4+

- Classify the following into physical or chemical changes: a) Rusting of iron b) Fermentation of palm wine c) Evaporation of a salt solution d) Melting of ice

EMPIRICAL AND MOLECULAR FORMULAE

Empirical formula is the formula which shows the simplest whole number ratios of atoms present in a compound while molecular formula is the formula which shows the actual number of each kind of atoms present in the molecule. The molecular formula of a compound is a whole number multiple of its empirical formulae.

Examples

- An organic compound on analysis yielded 2.04g carbon, 0.34g hydrogen and 2.73g oxygen.

- Calculate the empirical formula.

- If the relative molecular mass of the compound is 60. Calculate its molecular formula A.

Solution:

Elements C H Reacting mass 2.04 0.34 2.73

Mole ratio = Reacting mass = 2.04 : 0.34 : 2.73

Atomic mass 12 1 16

= 0.17: 0.34: 0.17

Dividing through by the 0.17: 0.34: 0.17

Smallest value 0.17 0.17 0.17

Whole number ratio 1: 2: 1

The empirical formula = CH2O

- Relative molecular mass of the compound = 60

Let the molecular formula = (CH2O)n

(CH2O)n = 60

(12 + 1×2 +16)n = 60

30n = 60

n = 60/30 = 2

Therefore, the molecular formula is (CH2O)2 = C2H4O2

- Calculate the empirical formula of an organic compound containing 81.8% carbon and 18.2% hydrogen

Solution:

Element C H

% Composition by mass 81.8 18.2

Mole ratio = % by mass = 81.8 : 18.2

Atomic mass 12 1

= 6.82: 18.2

Dividing through by the 6.82: 18.2

smallest value 6.82 6.82

Whole number ratio 1: 2.67

Since the ratio is not completely whole, we continue to multiply to obtain the lowest multiple that is close to a whole number i.e.

1:2.67, 2:5.34, 3:8.01, 4:10.65, 5:13.35, etC. 3:8.01 is close to the whole number.

Therefore, the empirical formula is C3H8

ASSIGNMENT

- An organic compound has the empirical formula CH2. If its molecular mass is 42gmol-1, what is the molecular formula?

- Determine the relative molecular mass of calcium trioxocarbonate (v).

- Define the term radical.

- Write the formula of the following compounds A. Mercury (i) dinitrate (iii) B.Sodium hydrogen trioxocarbonate (IV) C. Oxochlorate (I) acid

LAWS OF CHEMICAL COMBINATION

The 3 laws of chemical combination are:

- Law of conservation of mass

- Law of definite proportion or constant composition

- Law of multiple proportions

- LAW OF CONSERVATION MASS

This law states that during chemical reactions, matter can neither be created nor destroyed but changes from one form to another.

EXPERIMENT TO VERIFY THE LAW

AIM: To verify the law of conservation of mass

THEORY: The equation of the reaction chosen for study is as follows:

HCl(aq) + AgNO3(aq) → AgCl(s) + HNO3(aq)

White ppt

APPARATUS: Weighing balance, conical flask, small test tube, string cork stopper.

REAGENTS NEEDED: Solutions of HCl and AgNO3 stored in two different reagent bottles.

METHOD: The dilute HCl is poured into a conical flask. The small test tube is filled with solution and using a string tied around the neck of the test tube, it is suspended inside the conical flask containing the acid in such a way that the two solutions do not mix. The conical flask and its content are weighed using a weighing balance and the result is recorded. The two solutions are mixed by swirling the conical flask and the weight of the conical flask and its content is taken again.

RESULT: After mixing the two solutions, a white precipitate of AgCl was formed indicating that a chemical reaction has taken place.

DISCUSSION: The masses of the conical flask and its content before and after the reaction remained the same indicating that the mass of the reactants equal that of the products.

CONCLUSION: Since the two masses obtained are equal, it confirms that matter was not created nor destroyed during the chemical reaction.

LAW OF DEFINITE PROPORTION OR CONSTANT COMPOSITION

The law states that all pure samples of a particular chemical compound contain the same elements combined in the same proportion by mass.

EXPERIMENT TO VERIFY THE LAW

AIM: To verify the law of definite proportion

APPARATUS: Crucible, test tube, combustion boats, combustion tube, weighing balance, Bunsen burner, U-tube and two retort stands with clamps.

REAGENTS NEEDED: CuCO3 crystals, Na2CO3 solution, Cu(NO3)2 solution, dry hydrogen gas and CaCl2 crystals.

METHOD: Two samples of black CuO are prepared using different methods. Sample A is prepared by placing the CuCO3 crystals in a crucible and heating them strongly until they decompose into black CuO. The equation for the reaction is:

CuCO3(s) → CuO(s) + CO2(g)

Sample B is prepared by reacting a solution of Na2CO3 in a test tube with a solution of Cu(NO3)2. A green precipitate of CuCO3 is formed. This is filtered off and then heated strongly in a crucible to obtain black CuO. The equation for the reaction is:

Na2CO3(aq) + Cu(NO3)2 → CuCO3(s) + 2NaNO3(aq)

CuCO3(s) → CuO(s) + CO2(g)

The two samples of black CuO are placed in two dried and weighed combustion boats labelled A and B and weighed again. These boats are then placed in a combustion tube and heated. A stream of dry hydrogen is passed through the combustion tube to reduce the CuO to metallic Cu. After heating for some time, a reddish-brown residue shows that all the CuO has been reduced to metallic copper. The flame is removed but the passing of hydrogen gas continues to prevent the re-oxidation of the hot copper residues by atmospheric oxygen. Any water formed during the reaction is absorbed by the fused CaCl2 in the adjacent U-tube. When the boat is cool, the weight of it is taken. From the results, the percentage of Cu in each sample is calculated.

RESULT: Assuming the following result was obtained:

Sample A B

Mass of boat 3.16g 3.31g

Mass of boat + CuO 5.15g 5.29g

Mass of boat + Cu 4.76g 4.90g

Mass of CuO = (ii) – (i) 1.99g 1.98g

Mass of Cu = (iii) –(i) 1.60g 1.59g

% of Cu in CuO 1.60 x 100 1.59 x 100

1.99 1 1.98 1

80.40% 80.30%

Therefore, % of Cu in CuO is 80% 80%

% of O2 in CuO 20% 20%

DISCUSSION: The % of Cu residue in the two samples is approximately 80% irrespective of the method of preparation of the CuO samples.

CONCLUSION: In pure CuO, Cu and O are always present in a definite proportion by mass of approximately 4:1.

LAW OF MULTIPLE PROPORTIONS

This states that if two elements combine to form more than one compound, the masses of one of the elements which separately combine with the fixed mass of the other element are in a simple ratio

EXPERIMENT TO VERIFY THE LAW

AIM: To verify the law of multiple proportions

APPARATUS: Combustion boats, combustion tube, weighing balance, Bunsen burner, U-tube and retort stand with clamp

REAGENTS NEEDED: Cu2O crystals, CuO crystals, dry hydrogen gas and calcium chloride crystals

METHOD: The two boats are dried and weighed. Cu2O is placed in one and labelled A and CuO is placed in the other and labelled B. The two boats are weighed again and placed in a combustion tube to reduce the oxides to copper by passing hydrogen gas into the combustion tube. When the samples are cooled, the residues obtained are weighed.

RESULT: Assuming the following result was obtained:

Sample Cu2O CuO

Mass of sample (oxide) 3.04g 1.91g

Mass of Cu residue 2.55g 1.35g

Mass of oxygen removed from oxide 0.49g 0.53g

CALCULATION: Calculating the various masses of copper which combine separately with fixed mass (say 1g of oxygen)

For Cu2O,

0.49g of O2 combines with 2.55g of Cu

1.0g of O2 will combine with Xg of Cu

Xg of Cu = 2.55g x 1.0g

0.49g

= 5.20g

For CuO,

0.53g of O2 combines with 1.38g of Cu

1.0g of O2 will combine with Xg of Cu

Xg of Cu = 1.38g x 1.0g

0.53g

= 2.60g

Oxides of copper Cu2O CuO

Mass of copper 5.20g 2.60g

The ratio of copper 2: 1

CONCLUSION: The masses of copper which combine with a fixed mass of oxygen in Cu2O and CuO are in a simple ratio of 2:1.