Friction JSS2 Basic Technology Lesson Note

Download Lesson NoteTopic: Friction

FRICTION

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

- Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of two solid surfaces in contact. Dry friction is subdivided into static friction (“stiction”) between non-moving surfaces, and kinetic friction between moving surfaces. Except for atomic or molecular friction, dry friction generally arises from the interaction of surface features, known as asperities.

- Fluid friction describes the friction between layers of a viscous fluid that are moving relative to each other.

- Lubricated friction is a case of fluid friction where a lubricant fluid separates two solid surfaces.

- Skin friction is a component of drag, the force resisting the motion of a fluid across the surface of a body.

- Internal friction is the force resisting motion between the elements making up a solid material while it undergoes deformation.

When surfaces in contact move relative to each other, the friction between the two surfaces converts kinetic energy into thermal energy (that is, it converts work to heat). This property can have dramatic consequences, as illustrated by the use of friction created by rubbing pieces of wood together to start a fire. Kinetic energy is converted to thermal energy whenever motion with friction occurs, for example when a viscous fluid is stirred. Another important consequence of many types of friction can be wear, which may lead to performance degradation or damage to components. Friction is a component of the science of tribology.

Friction is desirable and important in supplying traction to facilitate motion on land. Most land vehicles rely on friction for acceleration, deceleration, and changing direction. Sudden reductions in traction can cause loss of control and accidents.

Friction is not itself a fundamental force. Dry friction arises from a combination of inter-surface adhesion, surface roughness, surface deformation, and surface contamination. The complexity of these interactions calculates friction from first principles impractical and necessitates the use of empirical methods for analysis and the development of theory.

Friction is a non-conservative force – work done against friction is path-dependent. In the presence of friction, some energy is always lost in the form of heat. Thus mechanical energy is not conserved.

Laws of dry friction

The elementary property of sliding (kinetic) friction was discovered by experiment in the 15th to 18th centuries and was expressed as three empirical laws:

- Amontons’ First Law: The force of friction is directly proportional to the applied load.

- Amontons’ Second Law: The force of friction is independent of the apparent area of contact.

- Coulomb’s Law of Friction: Kinetic friction is independent of the sliding velocity.

Dry friction

Dry friction resists the relative lateral motion of two solid surfaces in contact. The two regimes of dry friction are ‘static friction’ (“stiction”) between non-moving surfaces, and kinetic friction (sometimes called sliding friction or dynamic friction) between moving surfaces.

Coulomb friction, named after Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, is an approximate model used to calculate the force of dry friction. It is governed by the model:

F f ≤ μ F n , {\displaystyle F_{\mathrm {f} }\leq \mu F_{\mathrm {n} },}

where

- F f {\displaystyle F_{\mathrm {f} }\,} is the force of friction exerted by each surface on the other. It is parallel to the surface, in a direction opposite to the net applied force.

- μ {\displaystyle \mu \,} is the coefficient of friction, which is an empirical property of the contacting materials,

- F n {\displaystyle F_{\mathrm {n} }\,} is the normal force exerted by each surface on the other, directed perpendicular (normal) to the surface.

The Coulomb friction F f {\displaystyle F_{\mathrm {f} }\,} may take any value from zero up to μ F n {\displaystyle \mu F_{\mathrm {n} }\,}, and the direction of the frictional force against a surface is opposite to the motion that surface would experience in the absence of friction. Thus, in the static case, the frictional force is exactly what it must be to prevent motion between the surfaces; it balances the net force tending to cause such motion. In this case, rather than providing an estimate of the actual frictional force, the Coulomb approximation provides a threshold value for this force, above which motion would commence. This maximum force is known as traction.

The force of friction is always exerted in a direction that opposes movement (for kinetic friction) or potential movement (for static friction) between the two surfaces. For example, a curling stone sliding along the ice experiences a kinetic force slowing it down. For an example of potential movement, the drive wheels of an accelerating car experience a frictional force pointing forward; if they did not, the wheels would spin, and the rubber would slide backward along the pavement. Note that it is not the direction of movement of the vehicle they oppose, it is the direction of (potential) sliding between tire and road.

Normal force

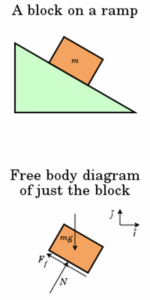

The free-body diagram for a block on a ramp. Arrows are vectors indicating directions and magnitudes of forces. N is the normal force, mg is the force of gravity, and Ff is the force of friction.

Main article: Normal force

The normal force is defined as the net force compressing two parallel surfaces together, and its direction is perpendicular to the surfaces. In the simple case of a mass resting on a horizontal surface, the only component of the normal force is the force due to gravity, where N = m g {\displaystyle N=mg\,}. In this case, the magnitude of the friction force is the product of the mass of the object, the acceleration due to gravity, and the coefficient of friction. However, the coefficient of friction is not a function of mass or volume; it depends only on the material. For instance, a large aluminum block has the same coefficient of friction as a small aluminum block. However, the magnitude of the friction force itself depends on the normal force, and hence on the mass of the block.

If an object is on a level surface and the force tending to cause it to slide is horizontal, the normal force N {\displaystyle N\,} between the object and the surface is just its weight, which is equal to its mass multiplied by the acceleration due to earth’s gravity, g. If the object is on a tilted surface such as an inclined plane, the normal force is less, because less of the force of gravity is perpendicular to the face of the plane. Therefore, the normal force, and ultimately the frictional force, is determined using vector analysis, usually via a free-body diagram. Depending on the situation, the calculation of the normal force may include forces other than gravity.

Coefficient of friction

The coefficient of friction (COF), often symbolized by the Greek letter µ, is a dimensionless scalar value that describes the ratio of the force of friction between two bodies and the force pressing them together. The coefficient of friction depends on the materials used; for example, ice on steel has a low coefficient of friction, while rubber on pavement has a high coefficient of friction. Coefficients of friction range from near zero to greater than one. It is an axiom of the nature of friction between metal surfaces that it is greater between two surfaces of similar metals than between two surfaces of different metals— hence, brass will have a higher coefficient of friction when moved against brass, but less if moved against steel or aluminum.

For surfaces at rest relative to each other μ = μ s {\displaystyle \mu =\mu _{\mathrm {s} }\,}, where μ s {\displaystyle \mu _{\mathrm {s} }\,} is the coefficient of static friction. This is usually larger than its kinetic counterpart. The coefficient of static friction exhibited by a pair of contacting surfaces depends upon the combined effects of material deformation characteristics and surface roughness, both of which have their origins in the chemical bonding between atoms in each of the bulk materials and between the material surfaces and any adsorbed material. The fractality of surfaces, a parameter describing the scaling behavior of surface asperities, is known to play an important role in determining the magnitude of static friction.

For surfaces in relative motion μ = μ k {\displaystyle \mu =\mu _{\mathrm {k} }\,} , where μ k {\displaystyle \mu _{\mathrm {k} }\,} is the coefficient of kinetic friction. The Coulomb friction is equal to F f {\displaystyle F_{\mathrm {f} }\,}, and the frictional force on each surface is exerted in the direction opposite to its motion relative to the other surface.

Arthur Morin introduced the term and demonstrated the utility of the coefficient of friction. The coefficient of friction is an empirical measurement – it has to be measured experimentally, and cannot be found through calculations. Rougher surfaces tend to have higher effective values. Both static and kinetic coefficients of friction depend on the pair of surfaces in contact; for a given pair of surfaces, the coefficient of static friction is usually larger than that of kinetic friction; in some sets, the two coefficients are equal, such as teflon-on-teflon.

Most dry materials in combination have friction coefficient values between 0.3 and 0.6. Values outside this range are rarer, but Teflon, for example, can have a coefficient as low as 0.04. A value of zero would mean no friction at all, an elusive property. Rubber in contact with other surfaces can yield friction coefficients from 1 to 2. Occasionally it is maintained that µ is always < 1, but this is not true. While in most relevant applications µ < 1, a value above 1 merely implies that the force required to slide an object along the surface is greater than the normal force of the surface on the object. For example, silicone rubber or acrylic rubber-coated surfaces have a coefficient of friction that can be substantially larger than 1.

While it is often stated that the COF is a “material property,” it is better categorized as a “system property.” Unlike true material properties (such as conductivity, dielectric constant, and yield strength), the COF for any two materials depends on system variables like temperature, velocity, atmosphere, and also what is now popularly described as aging and de-aging times; as well as on geometric properties of the interface between the materials, namely surface structure. For example, a copper pin sliding against a thick copper plate can have a COF that varies from 0.6 at low speeds (metal sliding against metal) to below 0.2 at high speeds when the copper surface begins to melt due to frictional heating. The latter speed, of course, does not determine the COF uniquely; if the pin diameter is increased so that the frictional heating is removed rapidly, the temperature drops, the pin remains solid and the COF rises to that of a ‘low speed’ test.